To celebrate Women’s History Month we are taking a look at the roles women played on the C&O Canal. Much of the canal’s history focuses on men, but thanks to the late Karen Gray, the C&O Canal National Historical Park’s former volunteer historian, we have this information on the canal’s women.

Most of our canal women appear in oral histories, newspaper reports, C&O Canal Company reports, and secondary sources from the period of 1903-1923, which appears to be the primary period of family boating.

In the canal’s operating era, a canal boat captain might have owned his own boat or operated his boat for its owner or a company. A common complaint is that the captains were not paid enough to hire labor, and as a result, they sometimes used family to avoid paying crews. Unpaid family labor is one of the main ways women became involved on the canal.

Locktenders

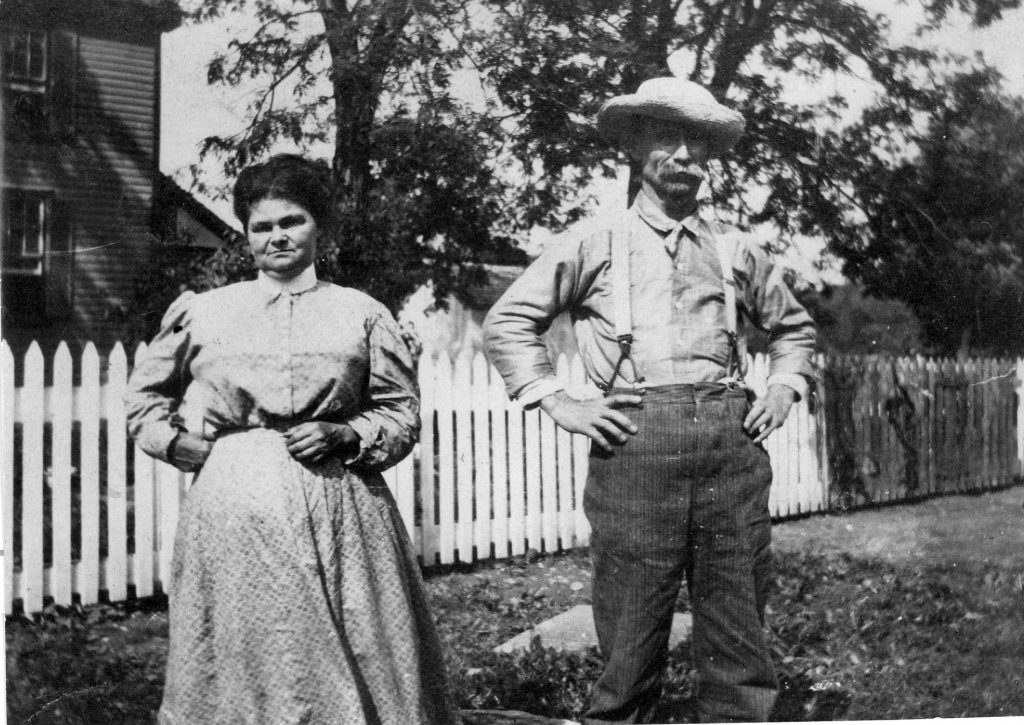

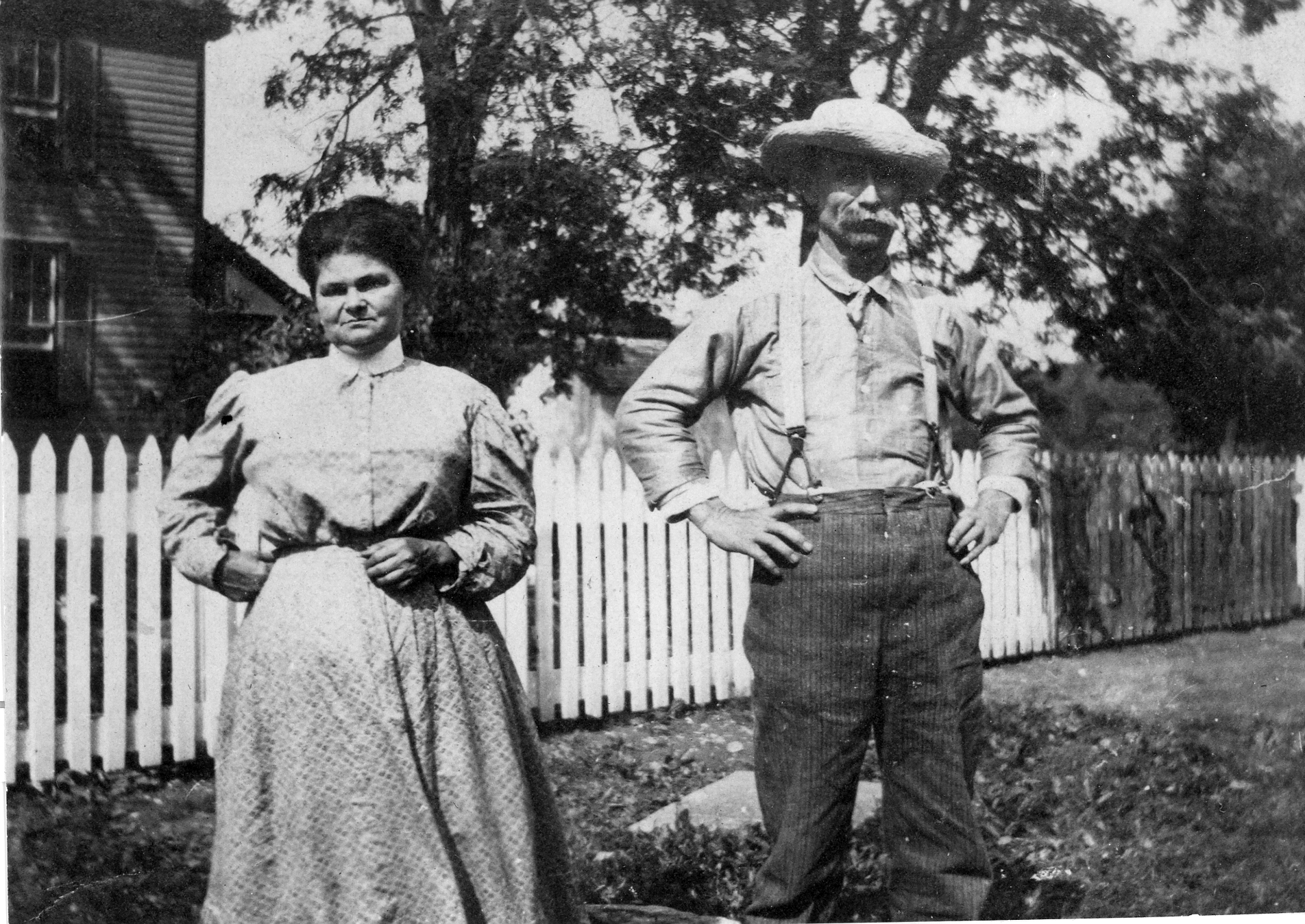

Locktenders were almost always married men as they tended to be more reliable than single men, and their families could serve as unpaid assistants. Many women likely served as unofficial locktenders, but there were also women officially appointed to the job, some when their husbands died or were drafted into the Civil War.

Eliza Page was appointed as lock keeper for Lock 23 when her husband died in 1835. In 1842, James O’Rilley, locktender to four locks in Georgetown, drowned in Lock 3. Twenty-one boatmen and citizens petitioned the board to appoint his wife, Mrs. O’Rilley, to the job instead of her adult son because she had a large family and young children. She was appointed to run the lock with her son’s support.

When George Hardy, who ran Locks 35 and 36 in Harpers Ferry, was drafted, his wife and children were allowed to operate the locks in his absence.

Another way to get appointed was after a party change. Canal company jobs were used as political payoffs, and thus, there was significant turnover when a new party was voted in. After a change in canal administration in June, 1860, the board replaced all of the locktenders, and two of the new appointees were women: Mrs. Adeleade Hill at Lock 12 and Mrs. Egan at Lock 60.

In March, 1835, the Board of the C&O Canal Company decided that all women locktenders would be discharged May 1 in the interest of a more efficient operation. Mary Ross asked to continue as the locktender of Locks 12-14, and the Board approved her request. The Board did the same for Elizabeth Burgess at Lock 11 with the stipulation that she hire an assistant. It’s not clear how many women locktenders were discharged after this order.

Lock keeping often involved keeping animals and tending large gardens both for themselves and for the sale of food to boat people. Whether an official locktender or not, this was a role women likely played in addition to other traditional women’s work of caring for the house and children.

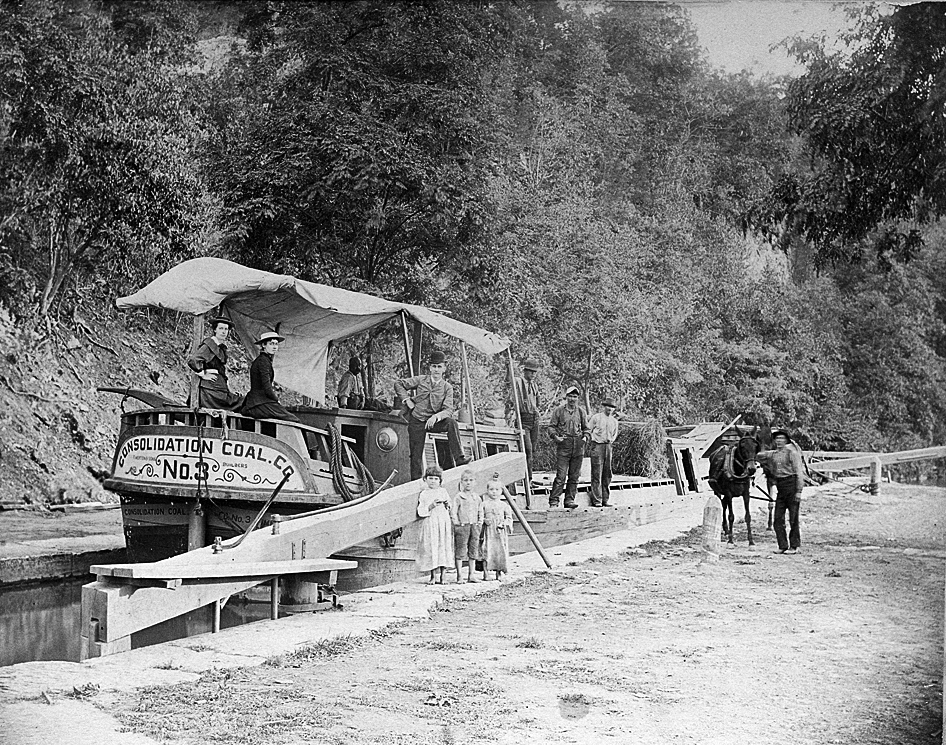

On Boats

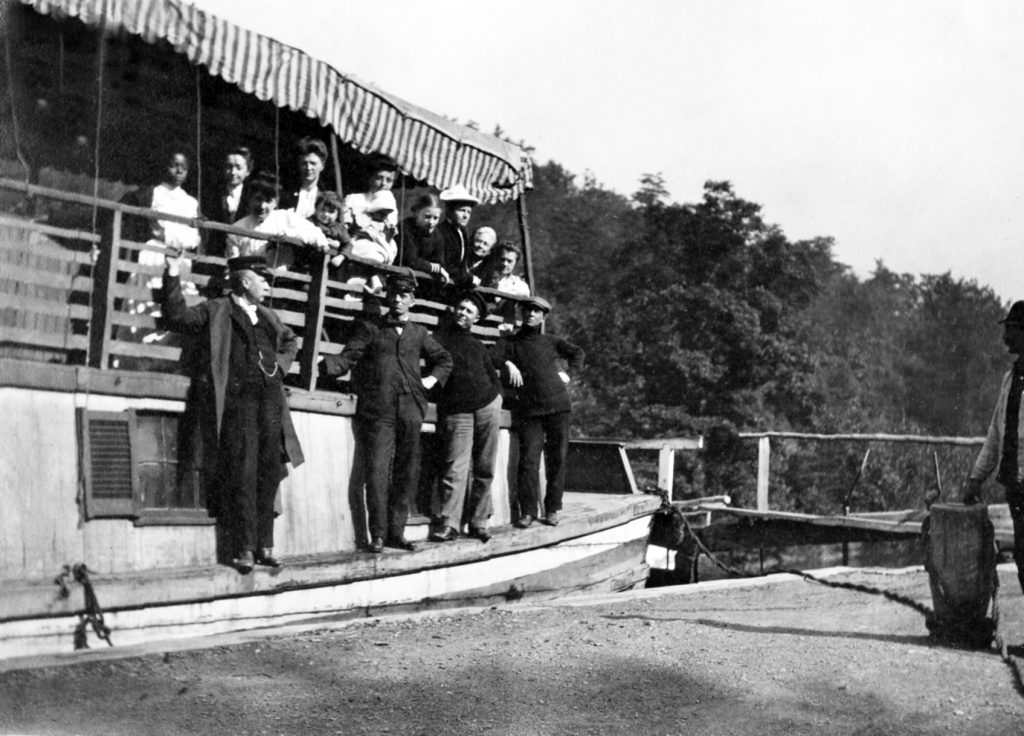

Women were hired as cooks for company maintenance crews on houseboats. One cook, Mrs. Null, successfully defended her houseboat against the attacks of General Early’s troops during the Civil War. Women worked on dance boats as dance partners and musicians and as servants and cooks on excursion boat trips. As is true with many canal workers, it is not always clear whether they were paid or if they were working for room and board.

Cases of women canal boat captains were rare, but it did happen. “Mis” Ziegler, Nancy McCoy, and Clara Dick all became captains after their husbands died. This was more common in later years, when families increasingly operated boats. In 1895, the Evening Star reported that five captains were women, two of which were widows and one whose husband was being held for murder.

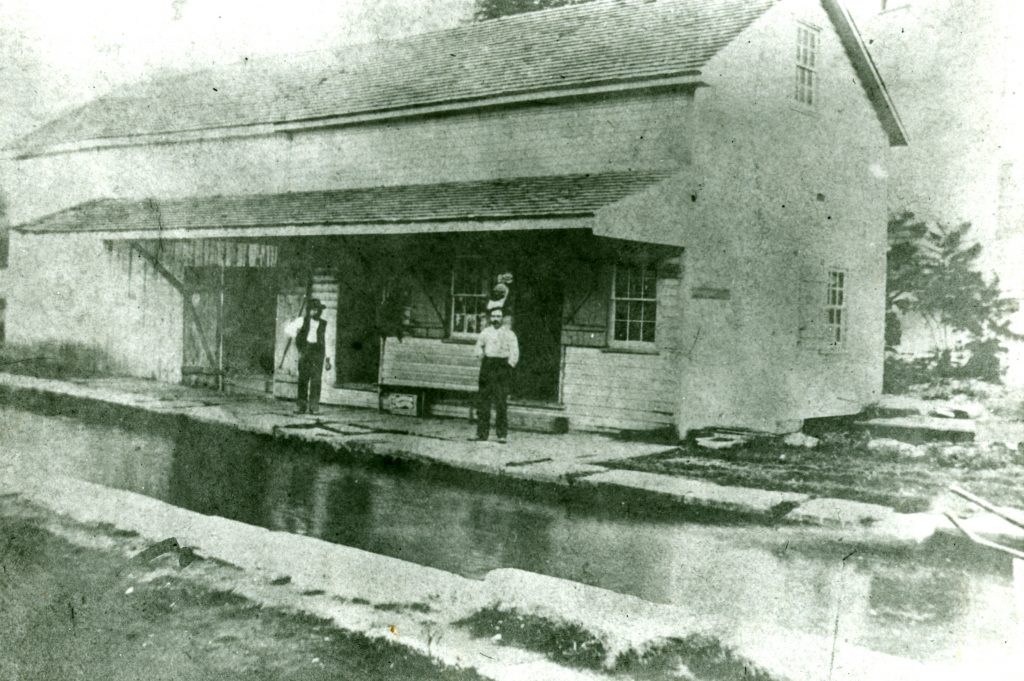

Entrepeneurs

In 1873, Mrs. M.A. Douglas rented land to build a feed store and to raise a large garden in the Seven Locks area. E.E. Jarboe ran a grocery, feed store, and post office at Lock 25. After he drowned in the lock, his two sons and daughter, Moselle, ran the store until it closed in 1906.

Passengers

In 1873, Mrs. Nellie Hammond (70) fell from a canal boat in Hancock and escaped from drowning. She was traveling from her home in Williamsport. Women were sometimes passengers on a working boat.

Other Reports

Since violence and death are likely to make the news, this is how we know about some of the women on the canal. There were many reports of drownings on the canal. In 1869, Nettie Turner (17), a cook, fell from a boat and drowned at Four Locks. In the early 1900s, Margaret Randolph and her son (10) drowned. At Lock 24, Katie Riley (3) drowned in 1905, and the family moved away from the river and canal to a house up the hill as a result. When a fight broke out between captain and locktender, the captain’s wife knocked one of the locktender’s sons off the boat.

Lavinia Waskey

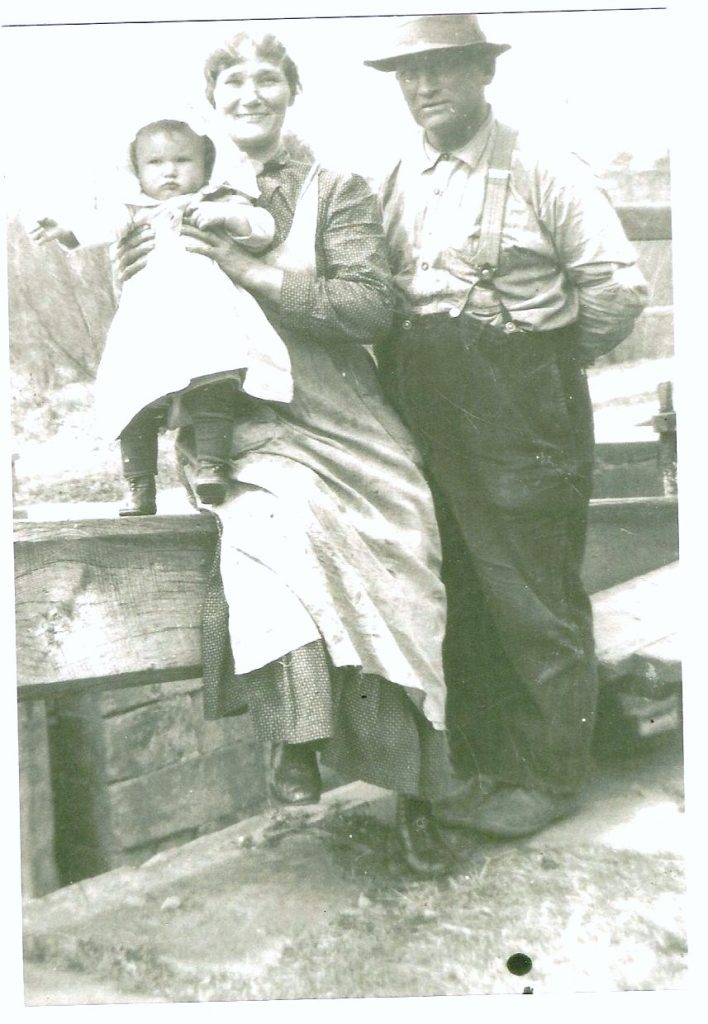

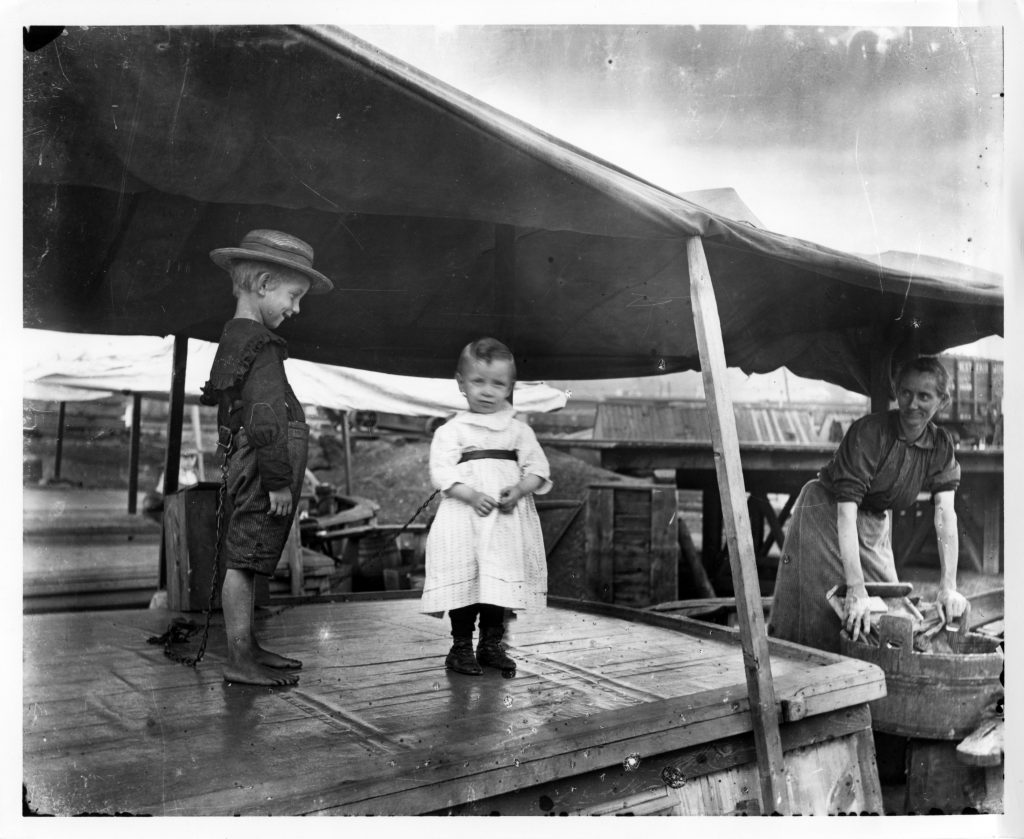

Lavinia’s father was a crewmember for Captain Hanes of Canal Towage Company Boat No. 20. When she was 2, her mother was also hired and allowed to bring Lavinia. Her father signed with Captain Hanes because Hanes would allow him to bring his wife and child along – an arrangement that meant the captain got “a cook and housekeeper”. We don’t know if Lavinia’s mother was paid.

Her father found work in the winter so they had food when there was no canal work. When she was three, she fell off the boat, badly cutting her chin. Lavinia’s father later became a lock tender at Lander Lock 29. Lavinia wrote how her mother was happy to have a real home. Her mother had to “put her back to the heavy lock gates to open them and get the boats through.” Lavinia’s story shows us that boat captains valued women as workers, although they may not have been compensated for their work. It also shows that working as a locktender likely provided a better life than working on a boat, and that women served as lock keepers even if they weren’t officially appointed.

Although wealthy women were more likely to travel by train, they were also occasional passengers on canal boats. The families that ran the canal were poor. Often they had no home except their boat, which they did not own. The women of the canal lived in a hard and dangerous world. Men were preferred for almost every job. The last few decades of the canal were run by families. Though their work often went unnoticed and was unpaid, women contributed to running the C&O Canal.