The C&O Canal National Historical Park (NHP) traces its existence as a recreational site to hundreds of young black men. These men, all of whom were out-of-work and between 18 and 25 years old, lived and worked at two camps (Camp NP-1 and Camp NP-2) operated by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), located along the canal near present-day Carderock Recreation Area from 1938-1942.

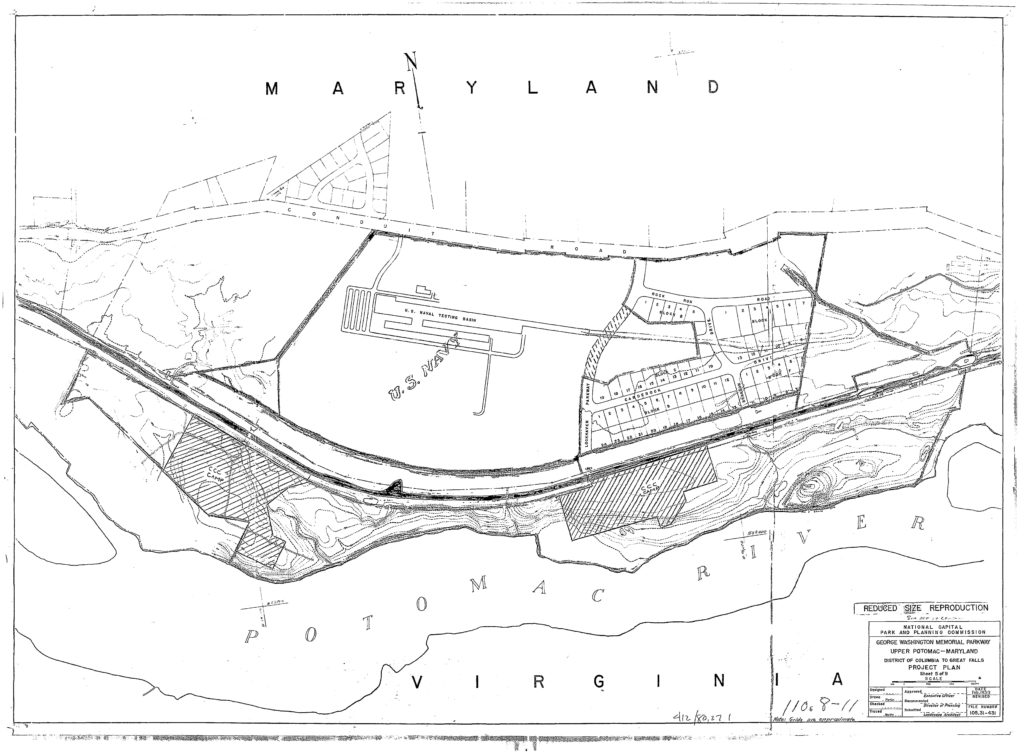

For four years, about 400 men worked five days a week, renovating the first twenty miles of canal property with special care given to the area around Great Falls. Within just two years, newspapers reported flowing water at Great Falls for the first time in sixteen years, thanks to CCC enrollees. They were also responsible for miles of waterway, telephone lines, and walking paths created all along the canal path.

Organizing these camps was not a quick process and was a culmination of at least fifteen years of planning, which started after the 1924 flood, when U.S. government officials discussed ways to acquire and utilize the largely-derelict canal property. The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 meant Federal funds dried up quickly as the government reduced spending, so plans for the C&O Canal were shelved for the time being.

The election of Franklin D. Roosevelt and announcement of New Deal programs changed that. The Public Works Administration (PWA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) promised massive amounts of manual labor, offering a way forward. After yet another flood, a lawsuit, and the intervention of both FDR and Eleanor Roosevelt, the government purchased the entire canal for $2,000,000 in early 1938, with another $500,000 set aside for parkway construction and canal rehabilitation. All parties signed a sales contract on August 6, 1938, thus allowing the federal government to deploy CCC enrollees to their new canal worksite.

Of special interest to most federal administrators was the area around the historic Great Falls Tavern and all areas below to Georgetown. New Deal administrators requested CCC administrators assign camps to the area in 1938 with the explicit intent to desilt and beautify the canal from Georgetown to Great Falls, roughly 14 miles, with an eye toward future public recreation.

As to why the CCC was chosen to do this work, the idea had been long discussed in government circles. In a 1934 correspondence with the Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, Frederic A. Delano, chairman of the National Capital Park and Planning Commission (NCP&PC) and FDR’s uncle, first floated the idea of using CCC labor to conserve and restore old canal locks and bridges to benefit the C&O Canal in an effort to extend the George Washington Memorial Parkway westward into Maryland.

A likely reason for selecting an African American company for the canal project was the minimal contact these camps would have with the general public. Administrators hinted at this when they requested CCC enrollees direct parking at Great Falls on Sundays, specifically requesting white CCC enrollees from a camp at Rock Creek, MD. Officials felt white enrollees were “better adapted for this work” – meaning there was a lower possibility of racist visitors causing a scene – and were willing to deal with the inconveniences of requesting Rock Creek enrollees rather than simply deploying a few African American men from Cabin John.

There are clearer reasons as to why these men were selected for the canal, specifically the men located at Camp NP-2 (Company 333). First, CCC officials working with Co. 333 while they were stationed in Wilderness, VA, reported a “very special and pressing need” at Civil War sites for “contact and guide service that might be met by white enrollees.” It is possible this request for a new white company was an excuse to shift the African American company out of the park, but there is no clear evidence to suggest this was the case. In addition, the men of Co. 333 gained experience at Wilderness doing the type of work required to restore a canal – conservation-minded landscaping, mass reshaping of earth, and renovating pathways for foot traffic.

Little is known about the men stationed at the canal camps. Lists of names are readily available, and a few men can be traced through later government records, but most men simply went back to their private lives after their CCC experience, leaving little documentation. Some, like Amos Custis from West Point, VA, left the CCC to join the military before returning from his tour to settle down permanently in Washington D.C.

Others had more tragic stories. Sidney Halsey of Covington, VA moved to Charleston, WV, after his time with Co. 333, where he remained unemployed for a few years. Halsey was one of the first men who signed up for the Selective Service draft on Oct. 16, 1940 and was likely assigned as an orderly within a hospital. Tragically, Halsey died on June 21, 1942 at the State Colored Tuberculosis Sanitarium in Denmar, WV, and is buried in Covington. Custis and Halsey knew each other for certain, both having served on the camp’s newspaper editorial staff when Co. 333 was stationed in Wilderness, VA.

There are other men, both black enrollees and white officers, connected with Co. 333 who we know a little about. Thomas Basknight Jr. went on to become a chief air traffic control officer in North Carolina; Leroy Barnard worked in the Department of Justice after World War II as an investigator for the Tokyo War Crimes trials; and Ralph Happel authored one of the first histories of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County Battlefields Memorial National Military Park in 1955. The full list of names for Co. 333 (Co. 325 enrollees are not known) is hosted on my personal website. If you are reading this and you recognized a name, please get in touch. All of these individuals have a story that is worth telling if we are willing to tell it.

The CCC and the C&O by Dr. Josh Howard, PhD

Click here to view Dr. Howard’s lecture on the CCC and the C&O Canal.

Read more articles about the CCC by Dr. Howard: